It would be inaccurate to say that the monks of Glenstal Abbey contributed to the establishment of our monastery in Nigeria, as if they were adding to something that already existed. In reality, they were the very foundation of monastic life at Saint Benedict’s Priory in Ewu-Esan in 1979. They did and were everything for us: erecting the first buildings, establishing plantations, recruiting and forming the initial community of monks, and raising the funds needed to feed, clothe, and train them.

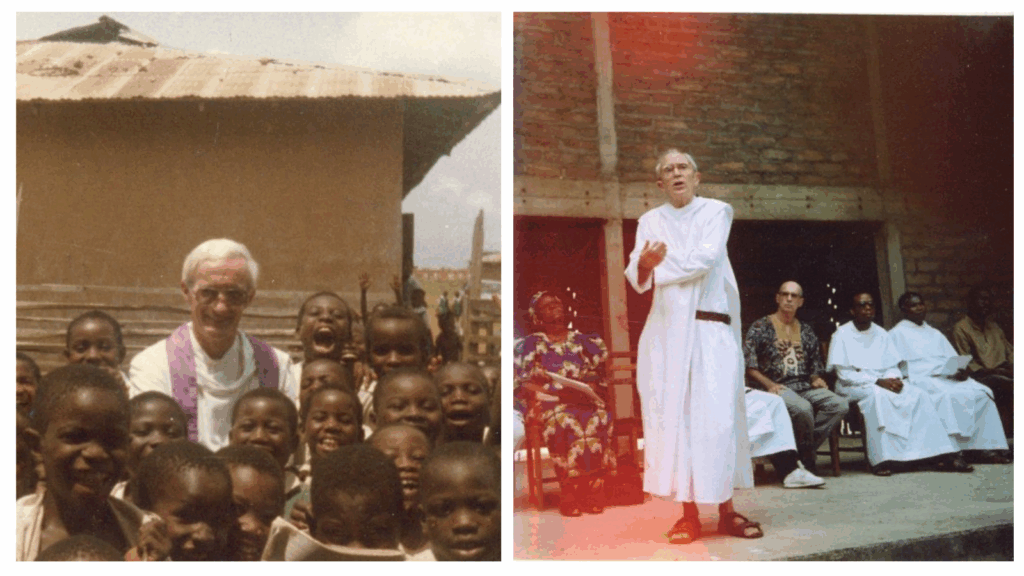

They were monks of vastly different gifts and personalities. They were mystics, philosophers, teachers, scholars, preachers, linguists, musicians, farmers, builders, and much more. Those pioneering early monks were popular in the locality whenever they went out to celebrate Mass, something which was appreciated by the local faithful and non-Christians alike.

When the monastery’s turquoise blue Volkswagen Beetle hit the road, the villagers would run and thunder excitedly: “Father! Father! Father!” irrespective of the driver. The car’s identification with the monastery was enough to cause a great stir among the locals, particularly as “Father” would often stop to give a lift to as many people as could be accommodated inside, outside and on-top of the little car as it bounced its way along the village roads.

Those early monks were all past middle age, and would even be considered elderly by African standards… I recall a local priest cautioning me against joining the community as he believed “the monastic life is meant for old and frustrated people.” They were certainly older men, but they were not frustrated. They came with energy and the common purpose of planting the monastic life in Nigeria. We were blessed in the following years to be visited by generations of Glenstal monks who helped us with formation, classes, music, retreats, and so on. They brought a new dynamism to the community, and their creativity contributed positively to the monastery’s outlook.

Looking back, one feels we owe those pioneering monks from Glenstal Abbey so much, especially for their efforts to establish an African monastery for Africans, rather than a community built along European lines here. It must have been a life of great sacrifice for these men, but it is one of the reasons they became revered and loved by all. Upon arrival, they observed local conditions and decided to go into agricultural work. They planted palm oil trees and – like local farmers – cultivated the yam, cassava, maize, plantain and melon which constitutes the diet of ordinary people, along with other vegetables and fruits like pawpaw, pineapple, bananas and oranges.

These Irishmen were used to potatoes and plenty of meat and fish, but soon they grew accustomed to eating mostly mashed yam and rice, with very tiny pieces of fish and meat during lunch on set days in the week. It was very obvious that they chose to identify with the local people, especially those at the margins of society. They soon began to resemble particularly impoverished Africans!

People didn’t see them as far off, distant, or unapproachable. Imagine the scene: many times a local woman would go into labour in the village, and her husband would run to the monastery in the middle of the night to call for help. One of the monks would appear, take out the famed turquoise blue Beetle and rush them to the hospital in the next town. It was run by Irish sisters, and the bill would be settled by the monks.

They lived simply, often precariously, and always close to the margins. They adopted what they could of African culture, and avoided imposing European ways onto the brothers. They guarded against the tribalism which is often common in African communities made up of members from different tribes, giving us today a strong community which is diverse yet unified.

These men were deeply convinced of their monastic calling, and they taught by their example of prayer, work, study and the common life. If the monastery were to fail today, it would be on our own heads and not on those of the Glenstal monks who made such a great sacrifice to create and hand over to us all that we have now. They laid the foundations in such a way that we, as native Africans, could shape the monastery with our own identity and culture. Abbot Augustine O’Sullivan would often remind us: “When the time comes, you Africans will decide for yourselves.”

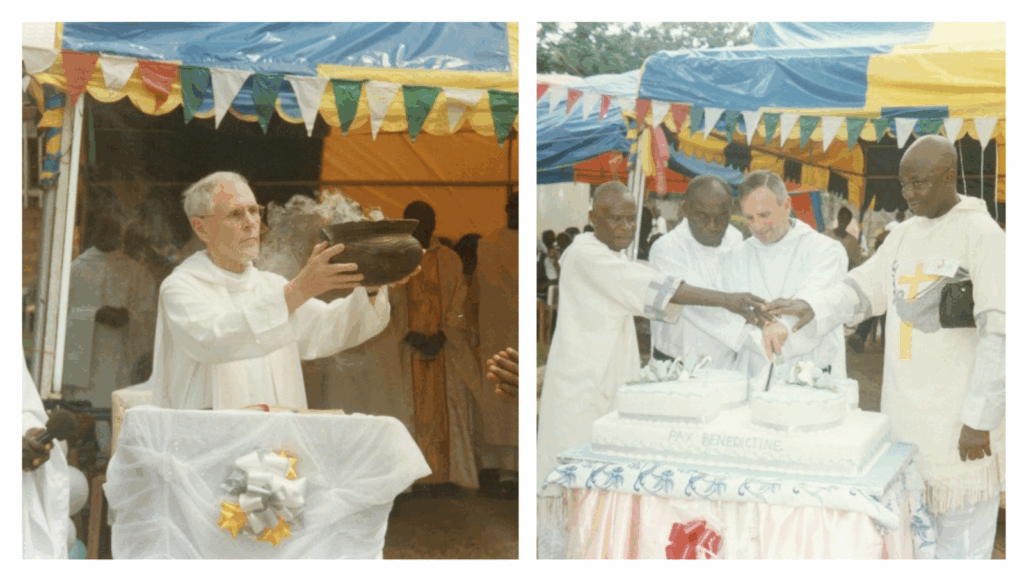

Today we are a community of over fifty monks from fifteen different Nigerian tribes, along with one Togolese confrère. The monastery’s layout resembles a traditional African village, with small residential blocks housing six monks each and a central building where the entire community gathers. The monastery’s architecture, liturgy and economic ventures all have an African feel to them. We seek to live a style of monastic life that is very much akin to the people and culture of this region, and a spirituality that the people of the place find no difficulty in identifying with and supporting.

There is a deliberate attempt to live a simple and pure monastic life, composed of the pillars of prayer, work and study in community. We rise each day at 3.30am with the beating of the Ekwe drum, before the day gets underway with a round of Vigils, time for personal prayer, and the celebration of Lauds and Mass from 5.30am. Between our daily work assignments we meet again in the church for communal prayer another four times during the course of the day, and retire to our cells sometime after 8pm. Our timetable is intense, as is the daily heat and humidity. There is time also for recreation and sports, and rarely is a brother absent from liturgy, table, work or community time.

During working hours monks can be found in the guesthouse or the herbal medicine centre, or at work in the bakery, candle factory or gift shop. We also run a farm of birds, pigs, goats, sheep and cattle, and have a palm oil plantation, vegetable garden and orchard.

The international press often reports on religious intolerance and violence by Islamic extremists in Nigeria, and we sometimes receive anxious calls and emails asking about our safety. While we have faced a few negative encounters with outsiders from other regions in the country, such incidents have been rare. Our monastery is located in Muslim territory, though the numbers of people following Islam, Christianity or Traditional African Religion are roughly the same. We have excellent relations with the local ruler and we find the Muslims here are very friendly.

At Ewu, all three religions interact and there is no real tension as it’s not unusual to find practitioners of all three among the members of a single family. The monastery plays a significant role as a common meeting ground for the followers of different religions. Here there is no segregation, no discrimination. When it is the time for their prayers, some of the Muslim workers simply create a space for themselves, do the ablutions and follow their prayer rituals. All of our workers, irrespective of the religion, attend Mass on major solemnities and join in the entertainment afterwards. The relationship between the monks and the people in neighbouring villages is very good.

During this World Mission Month, when the Church prays for and supports missionaries around the globe, I find myself reflecting on what the Irish monks brought to Ewu — and what we, in turn, might offer back to Glenstal Abbey and the Irish Church. Glenstal made many sacrifices to bring this foundation to birth and nurture it to maturity. If our motherhouse were to ask for help, we would not see it as repayment but as fulfilling our duty to a parent. In African culture, caring for one’s elders is a source of pride. Thus Saint Benedict’s Priory at Ewu will always remain open and grateful to Glenstal Abbey, remembering our founders and all who followed them in support of our growth.

We are both communities of individuals with names and stories, not faceless numbers. Ewu has a duty to keep our bond with Glenstal alive and fresh through regular communication and visits. We are also finding ways to honour the memory of each Irish monk who came to Ewu; the comprehensive list is quite long!

Every year, Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated as a solemnity at Ewu. On this great feast we give thanks to God for the Irish monks who came here, for our very existence through them, and for the entire Glenstal community. When I visit the motherhouse in Ireland, I never fail to go to the cemetery to pray for those who now sleep there, asking for their intercession so that the brilliant torch which Glenstal Abbey has handed on to us may never cease to burn brightly.

Peter Eghwrudjakpor OSB is superior of Saint Benedict’s Priory at Ewu-Esan in Edo State, Nigeria.