The above quotation from Frederick Douglass, the nineteenth century American slave turned abolitionist, testifies to the pleasure and value of reading. For Douglass it was patently true; the ability to decipher words on a page was key to his release and future success as a social reformer. However reading can yield deeper levels of freedom than that.

One can read for pure pleasure. Who has not stopped and savoured the first lines of some works of fiction! ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.’ (‘Pride and Prejudice’ by Jane Austen.) And the whole of Emily Bronte’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ has given aesthetic pleasure to generations of readers. The same can be said of ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ (by Steinbeck), ‘All the Light We Cannot See’ (by Anthony Doerr) and countless other novels. With them a reader thus ‘lives a thousand lives before he dies ….. [whilst] the man who never reads lives only one.’ Such ‘great reads’ introduce one to something deeper than aesthetics, they bring one to another place where one encounters other people and other predicaments. In time one learns to read a novel vertically as well as horizontally, and to understand literature not just as story but to value it for its ‘eternal freight’. This requires being open to literature as a study in depth of human nature from which we are enriched, rather than dismissing it as fanciful and to be replaced by a textbook of biology. But to read literature many of us require a teacher, either a formal one or an informal one and friend.

EXULTATION is the going

Of an inland soul to sea,—

Past the houses, past the headlands,

Into deep eternity!

Bred as we, among the mountains,

Can the sailor understand

The divine intoxication

Of the first league out from land? [1]

However for all the pleasure and companionship literature gives, and the voice it gives to man’s ultimate concerns, it is insufficient in responding to our search for meaning. The Bible indeed can be read for its literary quality alone: the Book of Esther for its epic plot, Second Isaiah and the Psalms for the beauty of their language, Sirac and Proverbs for their critical thinking, but to the believer these texts have another dimension; they resonate with something ‘other’, from beyond the horizon of everyday experience. These books have a character which is both human and divine. But while the reading the Bible is full of promise it is not easy to plumb its depths. At the most basic level the Jewish Rabbi, for example, does not see the Bible a narrative whole, in contrast to the Christian view. For him it is not a story of disaster in the Garden of Eden leading on to ultimate rescue, but a cryptic text (where no detail is unimportant) that offers guidance for life. For Christians it is a collection of books that does form a single whole and is unified by the New Testament. In this it testifies to Jesus as the Messiah and Son of God. To recognise this, and much more, one is best off when accompanied by a guide who can reveal its depth of meaning.

Christian tradition from earliest times has guided readers on four possible levels of meaning in scripture: first is the literal interpretation or what the author meant. This may not always be obvious as we run the risk of reading elements of our own cultural mindset into that of ancient times. As Origen said, taking the text on face value, as some people do, can be a sign of stupidity. (Whoever heard a snake speaking in Hebrew, as related in Genesis 3!). A second level of meaning is ethical; make the comparison between the Law of Moses and the teaching of Jesus from the Sermon on the Mount! A third level of scripture, termed ‘allegorical’, consists in taking people, places and things of scripture as pointing to realities on a higher plane in a symbolic world. The story of the good Samaritan has been read as representing Christ’s mission of salvation to all humanity. And finally, ‘anagogical’ interpretation detects mystical signs of the after life in biblical events and statements. In each level of interpretation Jesus Christ is shown to be the fulfliment of the Old Testament. A most ironic of all biblical passages is when Jesus, in the synagogue on the sabbath, having read from the scroll of Isaiah announces that “this text is being fulfilled today even while you are listening.” (Lk 4:16-22).

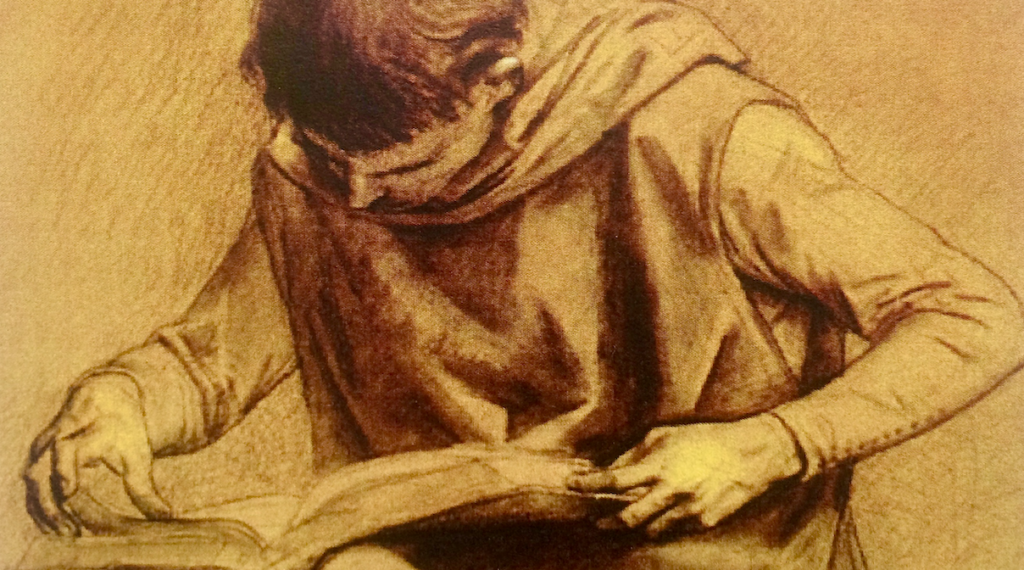

Monks have long approached the biblical literature along these lines though under the rubric of ‘Meditatio – Contemplatio – Oratio’. It is known as ‘Lectio Divina’. What could be better than to ruminate on the inspired scriptures so as to extract its divine essence, infused as it is through human words! For this kind of literature we may need a pedagogue! There are very many. Scripture commentaries come in varied user-friendly editions. Cf. footnotes for a few. [2]

Benedictine monks, at least during the season of Lent, ‘each receive a book from the library which they shall read through consecutively’. [3] If you too need guidance and encouragement in reading the Bible it may help to use a commentary or join a guided-reading group. It may set you on your path to freedom as a child of God, forever!

John O’Callaghan OSB

[1] Emily Dickinson

[2] ‘A History of the Bible’, by John Barton; Penguin Books 2020; ‘Jesus of Nazareth’ by Pope Benedict; Bloomsbury 2007; ‘The People’s Bible Commentary’ published by the Bible Reading Fellowship, Oxford; ‘Letter of HH Pope Francis on the Role of Literature in Formation’ ..

[3] Rule of Benedict; Chapter 48