We live in a time when the whole world is beginning to understand that our lives will have to be ‘at all times Lenten in character’ if we are to survive as a planet. There is a climate crisis which could destroy our world and a purification of the ecosystem is required, something like the traditional way of unclogging our spiritual ecosystem by prayer, fasting and almsgiving.

Since large-scale industrialization began around a century and a half ago, the levels of greenhouse gases have increased so that there is now an asphyxiating glut of greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere. Our oversupply of such emissions is creating a hole in the delicate mantilla which presently shades us from the sun, and we are wrecking the greenhouse which allows us to survive. We have become ‘oilaholics’ and the disease is contagious. Our addiction threatens to destroy the roof over our heads, so a programme of ecological transformation is needed fast.

Our spiritual ecosystem was routinely purified by prayer, fasting and almsgiving. These were the three-pronged approaches to Lent. Prayer puts us in touch with the ultimate source of divine energy in our lives, the Holy Spirit, breathing in our hearts; fasting allowed us to cut down on external energy consumption, to concentrate on being rather than having. It’s different for each one of us, and should mean giving up whatever is debilitating and switching to the alternative energy which will raise us from the dead.

Almsgiving provides an outlet for this newly sourced energy, allowing it to radiate into the atmosphere around us. Almsgiving is being generous as God is generous. And if you are guilt-ridden or spendthrift; if your weakness is not being able to say no to anyone, then your godlike generosity is to develop the backbone which can resist those grasping tentacles, cut off the prying tendrils and tell the creepy-crawlies to get lost. Lent is a time for getting rid of at least some of the crazy-makers in your life, those whom you allow to enslave you, importune you, take you for granted, bully you. Those who push you around, keep you under their thumb, act as travel agent for your guilt trips. Resurrection is not about being feak and weeble, an inexhaustible wimp, a pushover when it comes to those looking for a hand-out.

Too often the emphasis has been on mortification as an end in itself. Or it has come across as a rejection of the body, of the passions, of the sap of life, as if these were antipathetic to true Christian living. Asceticism is not a punitive discipline but rather like learning how to play a musical instrument or training ourselves in a worthwhile craft. It should not be miserable exercise of the will over a reluctant and frightened part of myself. Lent is about doing to death, mortifying, at least some of the things that prevent us from being. It is about renouncing at least one thing that weighs me down, holds me back and prevents me from rising from the dead. It is not a macho manifesto of the mind over the body. Christianity is not about self-conquest, it is about self-surrender. Surrender of the total person, body and soul, to the guidance of the Spirit.

Lent is the runway towards Easter, preparation for the fullest kind of life: its sign is joy, its source is love. It should make us more ready, more fit, more willing, more in shape, to rise with Christ from the tomb at Eastertide to be alive with him forever. As the poet Rilke says, ‘we shall have been marvellously prepared for divine relationship.’ In the end, this divine connection must surely transform us and our connection to one another and the world around.

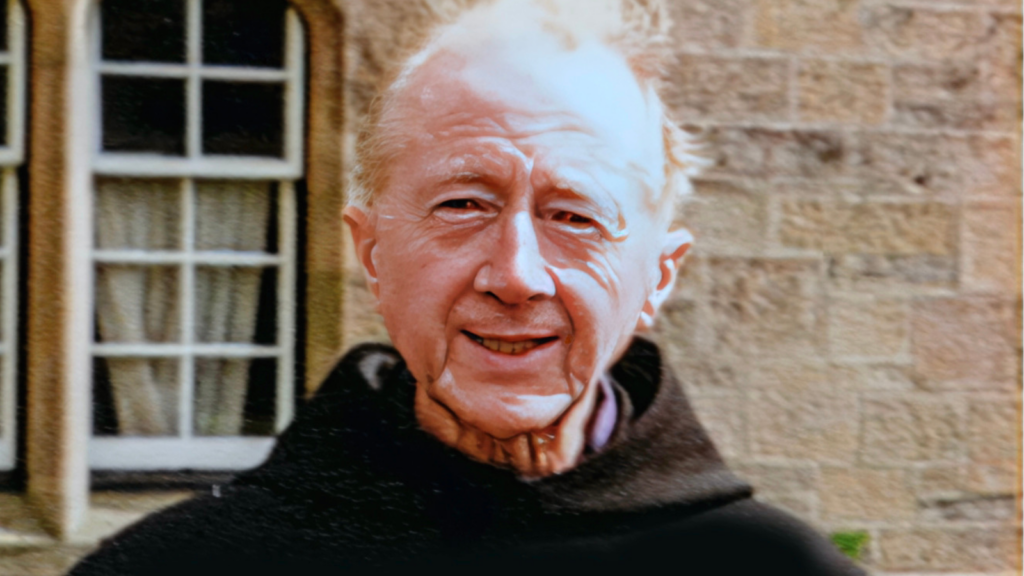

Mark Patrick Hederman OSB