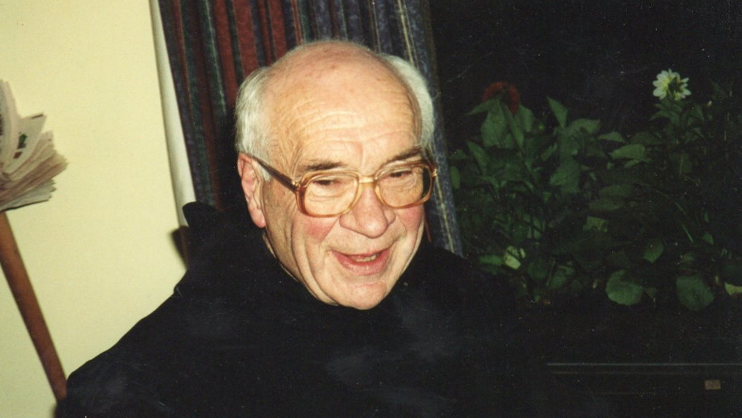

Fr. Henry O’Shea: ‘Paris is well worth a Mass.’

In 1592, after three years on the throne, King Henry IV of France, a vociferously avowed Protestant, guaranteed his grip on that throne by converting to Catholicism. On doing so, he is alleged to have quipped about Paris and its worth. A Mass.

Even if the king didn’t actually use these words, they sum up succicintly the cunning self-promoting cynicism which, from the beginning of time, has characterised many successful politicians. What matters is winning – at whatever the cost and regardless of human collateral damage. Does this sound familiar?

Today’s first reading from the prophet Isaiah, mentions the king, Ahaz, but supplies none of the back-story of this walking disaster who was King of Judah in the eighth century before Christ. To avoid having his rather small kingdom attacked by hostile neighbours and in particular, to avert a take-over by the regional super-power, Assyria, Ahaz instituted and promoted what was in effect a cultural surrender. He permitted and promoted a cultural colonisation. Does this sound familiar?

Earlier on in the Book of Isaiah, we hear of how Ahaz desecrated the Temple in Jerusalem, placing in it idols of the gods of neighbouring kingdoms and halting or disrupting traditional temple worship. He also, for the convenience of citizens and visitors, for passing trade, had shrines erected at street corners for devotional quickies. He explained that he was not so much denying the God of the Jews as practising what today is called inclusiveness by giving other gods and other religious outlooks a look-in. Whatever you’re having yourself…you know.

As so often, the compliant, conformist, opportunistic and indifferent in society went with the flow. We’re all the same really, aren’t we. And isn’t one set of beliefs really as good as any other? Or, as Frederick the Great of Prussia would declare twenty-four centuries later, ‘Everyone should be allowed to be saved in his – sorry, in their – own fashion.’ Isaiah tells us that Ahaz ducked the issue by refusing to oblige the Lord by asking for a sign. It was and usually is, too risky to put present compromises in jeopardy.

So, it is no wonder that Ahaz refuses to ask a sign of God. He is not really sure to which god he should turn. He is not really sure if there are actually any gods to which, to whom, he can turn. He ducks the issue by claiming that he would prefer not to put the God of Israel, the Lord, to the test.

While Isaiah is as capable of a bad-tempered rant as most other prophets, in this case he simply tells the House of David about a sign that it will get from the Lord: ‘Listen now, House of David! Not satisfied with trying human patience, will you try my God’s patience too? The Lord will give you a sign in any case. Look, the virgin is with child and will give birth to a son whom she will call Immanuel — God is with us.’ No explanation, no date, no century, no time-scale. Simply a promise.

Today’s gospel, by quoting the first reading, literally links up this promise with what we celebrate, with what we recall and look forward to every Advent and Christmas. Today’s gospel links this promise with what we celebrate, recall and look forward to at every liturgy – with what we celebrate, recall and look forward to all of our baptized lives. In his dream, Joseph is told just enough to make it possible for him to give his heart and soul.

Today’s second reading also describes, if only partly, who this Immanuel, this human descendant of David was, is and will be: Jesus Christ, the Son of God, ‘in all his power through his resurrection from the dead.’

Through his resurrection from the dead: that is, not by philosophical argument, not by political ideologising or activism, not by psychologising, not by magic, convenience, not by manipulability or mere usefulness. Importantly, too, not as the possession of any exclusive group, ethnic, cultural or cultic.

While Paul, in his letter to the Romans, affirms that he received grace and his apostolic mission to preach through Jesus Christ, he affirms simultaneously, that every nation, every people, every one of us, has received that grace and apostolic mission to preach the obedience of faith…. the listening to and spreading of message of the baptised heart and the living of its consequences.

And this grace and mission can be undertaken only when each one of us starts with her or his own heart as the recipietnt of grace and as mission territory. This Immanuel, this God-with-us, at every moment of our being is calling us to be Advent, to be Nativity, to be Epiphany, that is, to be always waiting for his coming, to be constantly reborn, to give witness to, to radiate, this coming and birth.

While there will always be an Ahaz in every one of us, and every one of us is our own Paris, Immanuel, God-with-us, certainly can and does make us well worth a Mass.