As we enter the New Year, my social media feed is full of advice on how to set and achieve goals for 2026, while my email inbox overflows with offers for gym equipment and self-improvement plans. But I’m not quite ready for all that — and perhaps you aren’t either.

If so, I’d like to draw your attention to a quiet gesture the Church offers in the upcoming feast of Epiphany: the singing of the Proclamation of the Date of Easter, sometimes called the calendar of movable feasts. After the Gospel, the Church solemnly announces the dates of Easter and the great feasts that flow from it. Time itself is named, blessed, and gently ordered around the mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection.

For those shaped by monastic life, this moment resonates deeply. Monasteries live by a calendar that is both intensely practical and profoundly theological. Bells ring, psalms return, seasons change, and feasts arrive whether we feel ready or not. The Epiphany proclamation reminds us that our lives are not simply a series of personal plans or private resolutions, but part of a shared rhythm — a common life in time.

There is something quietly countercultural about singing the year into being. Instead of asking, “What will I achieve?”, the Church asks, “How will we receive what is given?” As this New Year opens, rather than turning first to goal-setting videos or productivity advice, you might look instead to the singing of the Proclamation of the Movable Feasts from St Peter’s in Rome, where the year ahead is named and entrusted to God. In that same spirit, the dates of the movable feasts for 2026 are set out below, so you can take a screenshot and return to them when the year begins to unfold.

May we live this year, in all things, that God may be glorified.

Oscar McDermott OSB

The Year Ahead — Movable Feasts 2026

Ash Wednesday – 18 February

Easter Sunday – 5 April

Ascension of the Lord – 14 May

(in some dioceses celebrated on Sunday 17 May)Pentecost Sunday – 24 May

Corpus Christi – 7 June

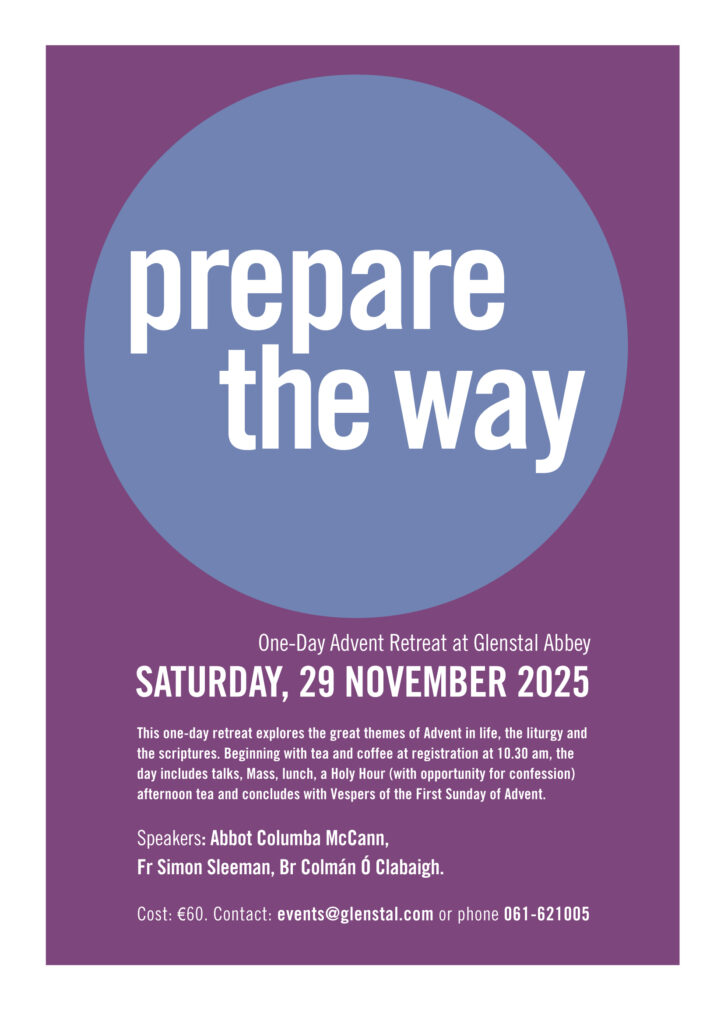

First Sunday of Advent – 29th of November